12 Min Read

Jan 24, 2018

Hypertension is the Biggest Cost Center Being Faced by Healthcare Today

Reducing blood pressure is the key to managing the exploding chronic disease crisis in the United States High blood pressure is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Over 33% of people above the age of 65 have high blood pressure.

Reducing blood pressure is the key to managing the exploding chronic disease crisis in the United States

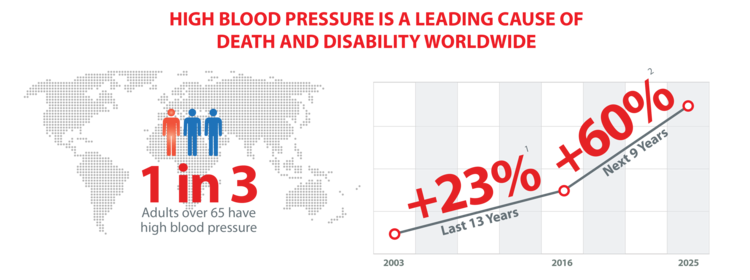

High blood pressure is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Over 33% of people above the age of 65 have high blood pressure. The rate of hypertension has increased by 23% in the last 13 years1 and is likely to increase by 60% till 2025.2 It is one of the leading cause of stroke and heart attack, increasing the risk by four times. In the last 13 years, the death rate due to hypertension has increased by 61%.1

It is difficult to treat as in 95% of cases there is no identifiable cause. Only 30% of people suffering from hypertension have it under control.3 Medication management is the most common form of therapy, but unfortunately, it is not entirely effective. Patients are often on more than one blood pressure medication, subjected to unwanted side effects, and have poor compliance.

It is estimated that the 2008 Per-Member-Per-Month (PMPM) cost of adults with hypertension was about $716 – almost three times the $250 PMPM of adults without hypertension3. Thus there is a great opportunity to save lives. Dr. John Sotos, a cardiologist and worldwide medical director at Intel, identified that ‘Hypertension is mobile health's biggest opportunity.'4

A study in The New England Journal of Medicine showed that reducing systolic blood pressure from the current recommendation of below 150mmHg Sys to 120mmHg lowered the risk of heart failure by 38%, risk of death by a cardiac event by 43% and the risk of death for any other reason by 27%.5

Because white coat and masked hypertension readings make diagnosis and treatment difficult, regular monitoring of blood pressure readings is needed to manage it properly. Cardiowell works by remotely monitoring and managing blood pressure and medications while empowering individuals to manage their stress and increase their wellness

Blood Pressure Monitoring Management

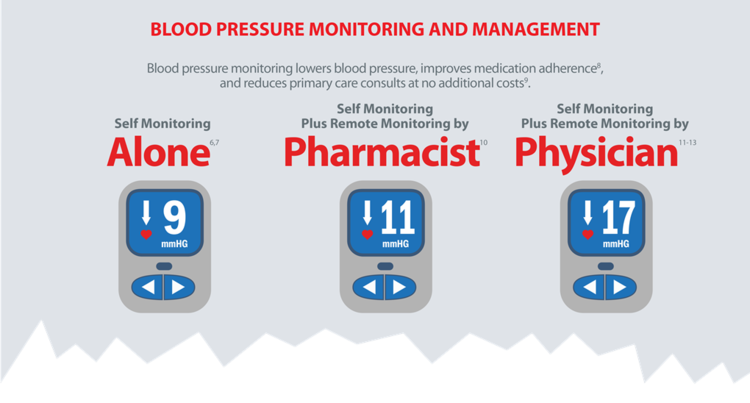

Self-monitoring has been shown to reduce BP by 3.4-8.9 mmHg (Sys)6, 7 improve adherence to antihypertensive medication8, and reduce primary care consultation rates at no additional cost. 9

Research also shows that remote monitoring and management of blood pressure by pharmacists can reduce blood pressure by 10.7 mmHg (Sys).10 Other studies that add a telemonitoring component have also witnessed blood pressure drop by as much as 17 mmHg.11-13

Cardiowell’s ‘always connected’ blood pressure devices and weight scales automate data collection. Results are sent from the device over a secure cellular network making results immediately available to clinical pharmacists trained to make treatment recommendations.

Cardiowell also collects additional indicators and predictors of cardiac health such as heart rate and heart rate variability.14 Cardiowell analyses minute fluctuations between each heart beat (heart rate variability) to quantify person’s wellness and provide greater insight into cardiac health.

Heart rate variability (HRV) is considered one of the best single indicators of person’s health and an early indicator of sudden death.15 By measuring HRV over time, along with other vital signs such as blood pressure, Cardiowell helps to understand when a person is at increased risk.

Stress Management and Increased Wellness

Research suggests that stress plays a significant role in hypertension,16-22 and increases the risk of heart attacks and stroke.22-23 Many studies have shown that biofeedback based breathing exercises can reduce blood pressure by as much as 15 mmHg. 24-50 Meditation which uses breathing techniques have been shown to reduce death by cardiac events in hypertensive patients by 30%.51

Breathing and mindfulness solutions are being promoted by Blue Cross, Etna, and Kaiser because of the known benefits. The American Heart Association also recommends device-guided breathing for anyone with high blood pressure.52

Breathing at six breaths per minute has been shown to increase heart rate variability and strengthen the body’s ability to regulate blood pressure.25, 53 It works by stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system and improves synchronization of the cardiac and respiratory systems. Evidence suggests that it is also very effective in alleviating depression,54-56 a major risk factor in heart disease.

Normal respiration rate is about 12 breaths per minute (bpm), yet most people breathe at 18 bpm. Fast breathing is known to stimulate the sympathetic nervous system which over time can strain the cardiovascular system. Respiration rate, much like heart rate, is a marker for pulmonary dysfunction.

Using mindfulness principles, Cardiowell increases a person's wellness by helping them breathe slower. Over time with increased awareness and better breathing, people's wellbeing increases and their blood pressure becomes more stable.

Cardiowell Solution

Cardiowell combines remote monitoring and medication management with wellness and mindfulness to lower blood pressure. Cardiowell expects to help lower blood pressure from at least 140/90 mmHg to the newly recommended 120/80 mmHg. Based on research, this is projected to help reduce the rate of stroke by around 25% and heart attacks by 20%.5

The greatest predictor of a second heart attack or stroke is having uncontrolled blood pressure. Cardiowell can also be used by patient-centered homes allowing chronic disease patients and post-acute patients to be remotely cared for. Patients benefit from having to take fewer medications thus decreasing the number of side effects, while at the same time it helps payers reduce population risks and costs.

Cardiowell is available today for employers and consumers as part of a physician-led care plan to help reduce the risks associated with hypertension. Learn more at www.cardiowell.io

Download the PDF version of the article here:

References:

1. Kung, H. C., & Xu, J. (2015). Hypertension-related Mortality in the United States, 2000-2013. NCHS data brief, (193), 1-8. View article

2. Chockalingam, A., Campbell, N. R., & Fodor, J. G. (2006). Worldwide Epidemic of Hypertension. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 22(7), 553-555. View article

3. Milliman Client Report(2005). The Need for Better Hypertension Control: Addressing Gaps in Care with the Medical Home Model. Milliman, Inc., NY. View article

4. Comstock, J. (2015). Intel's Medical Director: Hypertension is Mobile Health's Biggest Opportunity. View article

5. SPRINT Research Group. (2015). A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. N Engl J Med, 2015(373), 2103-2116. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511939. View article

6. Uhlig, K., Patel, K., Ip, S., Kitsios, G. D., & Balk, E. M. (2013). Self-measured blood pressure monitoring in the management of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine, 159(3), 185-194. View article

7. Fletcher, B. R., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Hinton, L., & McManus, R. J. (2015). The effect of self-monitoring of blood pressure on medication adherence and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of hypertension, hpv008. View article

8. Ogedegbe, G., & Schoenthaler, A. (2006). A systematic review of the effects of home blood pressure monitoring on medication adherence. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 8(3), 174-180. View article

9. McManus, R. J., Mant, J., Roalfe, A., Oakes, R. A., Bryan, S., Pattison, H. M., & Hobbs, F. R. (2005). Targets and self monitoring in hypertension: randomised controlled trial and cost effectiveness analysis. Bmj, 331(7515), 493. View article

10. Margolis, K. L., Asche, S. E., Bergdall, A. R., Dehmer, S. P., Groen, S. E., Kadrmas, H. M., ... & O’Connor, P. J. (2013). Effect of Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring and Pharmacist Management on Blood Pressure Control: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 310(1), 46-56. DOI:10.1001/JAMA.2013.6549. View article

11. Neumann, C. L., Menne, J., Schettler, V., Hagenah, G. C., Brockes, C., Haller, H., & Schulz, E. G. (2015). Long-Term Effects of 3-Month Telemetric Blood Pressure Intervention in Patients with Inadequately Treated Arterial Hypertension. Telemedicine and E-Health, 21(3), 145-150. DOI: 10.1089/TMJ.2014.0058. View article

12. Zullig, L. L., Melnyk, S. D., Goldstein, K., Shaw, R. J., & Bosworth, H. B. (2013). The Role of Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring in Managing Hypertensive Populations. Current Hypertension Reports, 15(4), 346-355. View article

13. Neumann, C. L., Menne, J., Rieken, E. M., Fischer, N., Weber, M. H., Haller, H., & Schulz, E. G. (2011). Blood Pressure Telemonitoring is Useful to Achieve Blood Pressure Control in Inadequately Treated Patients with Arterial Hypertension. Journal of Human Hypertension, 25(12), 732-738. View article

14. Fournier, J. C., DeRubeis, R. J., Hollon, S. D., Dimidjian, S., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., & Fawcett, J. (2010). Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity: A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. JAMA, 303(1), 47-53. View article

15. Ogliari, G., Mahinrad, S., Stott, D. J., Jukema, J. W., Mooijaart, S. P., Macfarlane, P. W., ... & Sabayan, B. (2015). Resting Heart Rate, Heart Rate Variability and Functional Decline in Old Age. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(15), E442-E449. DOI:10.1503/CMAJ.150462. View article

16. Linden, W. (1984). Psychological Perspectives of Essential Hypertension: Etiology, Maintenance, and Treatment (Vol. 3). Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers.

17. Shapiro, A. P. (1996). Hypertension and Stress: A Unified Concept. Psychology Press.

18. Steptoe, A. (1986). Stress Mechanisms in Hypertension. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 62(729), 697-699. View article

19. Henry, J. P., Stephens, P. M., & Ely, D. L. (1986). Psychosocial Hypertension and the Defence and Defeat Reactions. Journal of Hypertension, 4(6), 687-688. View article

20. Markovitz, J. H., Matthews, K. A., Kannel, W. B., Cobb, J. L., & D'Agostino, R. B. (1993). Psychological Predictors of Hypertension in the Framingham Study: Is There Tension In Hypertension?. JAMA, 270(20), 2439-2443. View article

21. Gasperin, D., Netuveli, G., Dias-da-Costa, J. S., & Pattussi, M. P. (2009). Effect of Psychological Stress on Blood Pressure Increase: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 25(4), 715-726. View article

22. Tawakol, A., Ishai, A., Takx, R. A., Figueroa, A. L., Ali, A., Kaiser, Y., ... & Tang, C. Y. (2017). Relation Between Resting Amygdalar Activity And Cardiovascular Events: A Longitudinal And Cohort Study. The Lancet, 389(10071), 834-845. View article

23. American Heart Association (2014). High Stress, Hostility, Depression Linked with Increased Stroke Risk. View article

24. Lin, G., Xiang, Q., Fu, X., Wang, S., Wang, S., Chen, S., ... & Wang, T. (2012). Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Decreases Blood Pressure in Prehypertensive Subjects by Improving Autonomic Function and Baroreflex. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(2), 143-152. View article

25. Gevirtz, R. (2013). The Promise of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback: Evidence-Based Applications. Biofeedback, 41(3), 110-120. View article

26. Reinke, A., Gevirtz, R., & Mussgay, L, (2007). Effects of Heart Rate Variability Feedback in Reducing Blood Pressure [Abstract]. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 32, 134.

27. Wang, S. Z., Li, S., Xu, X. Y., Lin, G. P., Shao, L., Zhao, Y., & Wang, T. H. (2010). Effect of Slow Abdominal Breathing Combined with Biofeedback on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Variability in Prehypertension. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(10), 1039-1045. View article

28. Schein, M. H., Gavish, B., Herz, M., Rosner-Kahana, D., Naveh, P., Knishkowy, B., ... & Melmed, R. N. (2001). Treating Hypertension with a Device That Slows and Regularises Breathing: A Randomised, Double-Blind Controlled Study. Journal of Human Hypertension, 15(4), 271. View article

29. Yucha, C. B., Clark, L., Smith, M., Uris, P., LaFleur, B., & Duval, S. (2001). The Effect of Biofeedback in Hypertension. Applied Nursing Research, 14(1), 29-35. View article

30. Linden, W., & Moseley, J. V. (2006). The Efficacy of Behavioral Treatments for Hypertension. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(1), 51-63. View article

31. Grossman, E., Grossman, A., Schein, M. H., Zimlichman, R., & Gavish, B. (2001). Breathing-Control Lowers Blood Pressure. Journal of Human Hypertension, 15(4), 263. View article

32. Rosenthal, T., Alter, A., Peleg, E., & Gavish, B. (2001). Device-Guided Breathing Exercises Reduce Blood Pressure: Ambulatory and Home Measurements. American Journal of Hypertension, 14(1), 74-76. View article

33. Meles, E., Giannattasio, C., Failla, M., Gentile, G., Capra, A., & Mancia, G. (2004). Nonpharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension by Respiratory Exercise in the Home Setting. American Journal of Hypertension, 17(4), 370-374. View article

34. del Paso, G. A. R., Cea, J. I., González-Pinto, A., Cabo, O. M., Caso, R., Brazal, J., ... & González, M. I. (2006). Short-Term Effects of a Brief Respiratory Training on Baroreceptor Cardiac Reflex Function in Normotensive and Mild Hypertensive Subjects. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 31(1), 37-49. View article

35. Elliott, W. J., Izzo, J. L., White, W. B., Rosing, D. R., Snyder, C. S., Alter, A., ... & Black, H. R. (2004). Graded Blood Pressure Reduction in Hypertensive Outpatients Associated with Use of a Device to Assist with Slow Breathing. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 6(10), 553-559. View article

36. Bertisch, S. M., Schomer, A., Kelly, E. E., Baloa, L. A., Hueser, L. E., Pittman, S. D., & Malhotra, A. (2011). Device-Guided Paced Respiration as an Adjunctive Therapy for Hypertension in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36(3), 173-179. View article

37. Nolan, R. P., Floras, J. S., Harvey, P. J., Kamath, M. V., Picton, P. E., Chessex, C., ... & Talbot, D. (2010). Behavioral Neurocardiac Training in Hypertension. Hypertension, 55(4), 1033-1039. DOI: 10.1161/HYPERTENSION-AHA.109.146233. View article

38. Viskoper, R., Shapira, I., Priluck, R., Mindlin, R., Chornia, L., Laszt, A., ... & Alter, A. (2003). Nonpharmacologic Treatment of Resistant Hypertensives by Device-Guided Slow Breathing Exercises. American Journal of Hypertension, 16(6), 484-487. View article

39. García-Vera, M. P., Labrador, F. J., & Sanz, J. (1997). Stress-Management Training for Essential Hypertension: A Controlled Study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 22(4), 261-283. DOI:10.1023/A:1022248029463. View article

40. Parati G, Izzo JL Jr, Gavish B., Third Edition. JL Izzo and HR Black, Eds. (2003). Respiration and Blood Pressure. Hypertension Primer (Ch. A40, p117-120). Baltimore, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

41. Hering, D., Kucharska, W., Kara, T., Somers, V. K., Parati, G., & Narkiewicz, K. (2013). Effects of Acute and Long-Term Slow Breathing Exercise on Muscle Sympathetic Nerve Activity in Untreated Male Patients with Hypertension. Journal of Hypertension, 31(4), 739-746. View article

42. Modesti, P. A., Ferrari, A., Bazzini, C., & Boddi, M. (2015). Time Sequence of Autonomic Changes Induced by Daily Slow-Breathing Sessions. Clinical Autonomic Research, 25(2), 95-104. DOI:10.1007/s10286-014-0255-9. View article

43. Joseph, C. N., Porta, C., Casucci, G., Casiraghi, N., Maffeis, M., Rossi, M., & Bernardi, L. (2005). Slow Breathing Improves Arterial Baroreflex Sensitivity and Decreases Blood Pressure in Essential Hypertension. Hypertension, 46(4), 714-718. View article

44. Elliott, W. J., & Izzo Jr, J. L. (2006). Device-Guided Breathing to Lower Blood Pressure: Case Report and Clinical Overview. Medscape General Medicine, 8(3), 23. View article

45. Wang, S. Z., Li, S., Xu, X. Y., Lin, G. P., Shao, L., Zhao, Y., & Wang, T. H. (2010). Effect of Slow Abdominal Breathing Combined with Biofeedback on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Variability in Prehypertension. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(10), 1039-1045. DOI: 10.1089/acm.2009.0577. View article

46. Brook, R. D., Appel, L. J., Rubenfire, M., Ogedegbe, G., Bisognano, J. D., Elliott, W. J., ... & Rajagopalan, S. (2013). Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure. Hypertension, 61(6), 1360-1383. DOI: 10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. View article

47. Benson, H., Marzetta, B., Rosner, B., & Klemchuk, H. (1974). Decreased Blood-Pressure in Pharmacologically Treated Hypertensive Patients Who Regularly Elicited the Relaxation Response. The Lancet, 303(7852), 289-291. View article

48. Irvine, M. J., Johnston, D. W., Jenner, D. A., & Marie, G. V. (1986). Relaxation and Stress Management in the Treatment of Essential Hypertension. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 30(4), 437-450. View article

49. Patel, C. (1975). 12-Month Follow-Up of Yoga and Bio-Feedback in the Management of Hypertension. The Lancet, 305(7898), 62-64. View article

50. Howorka, K., Pumprla, J., Tamm, J., Schabmann, A., Klomfar, S., Kostineak, E., ... & Sovova, E. (2013). Effects of Guided Breathing on Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Variability in Hypertensive Diabetic Patients. Autonomic Neuroscience, 179(1), 131-137. View article

51. Schneider, R. H., Alexander, C. N., Staggers, F., Rainforth, M., Salerno, J. W., Hartz, A., ... & Nidich, S. I. (2005). Long-Term Effects of Stress Reduction on Mortality in Persons≥ 55 Years of Age with Systemic Hypertension. The American Journal of Cardiology, 95(9), 1060-1064. View article

52. Brook, R. D., Appel, L. J., Rubenfire, M., Ogedegbe, G., Bisognano, J. D., Elliott, W. J., ... & Rajagopalan, S. (2013). Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure. Hypertension, 61(6), 1360-1383. DOI: 10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. View article

53. Lehrer, P. M., & Gevirtz, R. (2014). Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback: How and Why Does it Work?. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 756. View article

54. Fournier, J. C., DeRubeis, R. J., Hollon, S. D., Dimidjian, S., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., & Fawcett, J. (2010). Antidepressant Drug Effects and Depression Severity: A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. JAMA, 303(1), 47-53. View article

55. Kirsch, I., Deacon, B. J., Huedo-Medina, T. B., Scoboria, A., Moore, T. J., & Johnson, B. T. (2008). Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med, 5(2), e45. View article

56. Turner, E. H., Matthews, A. M., Linardatos, E., Tell, R. A., & Rosenthal, R. (2008). Selective Publication of Antidepressant Trials and Its Influence on Apparent Efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(3), 252-260. View article